https://www.sgr.org.uk/resources/did-cop26-deliver-thoughts-scientists-global-responsibility

Andrew Simms, Philip Webber, Stuart Parkinson, and Jan Maskell give their initial thoughts on the outputs of the COP26 climate negotiations – and examine some options for future action.

17 November 2021

Contents

The Glasgow Climate Pact: Half full or half empty? – Andrew Simms

The exceptionalism of the rich continues to fuel the climate crisis – Philip Webber

British sleight-of-hand disguises a lack of ambition – Stuart Parkinson

Behaviour change: a missed opportunity – Jan Maskell

The Glasgow Climate Pact: Half full or half empty?

Andrew Simms

Reading snap assessments of the outcomes from COP26 from observers whose integrity your respect, it is entirely possible to believe two things at the same time: that there has been a fundamental betrayal of civilisation’s survival chances, and that things could have gone worse.

If that represents a kind of cognitive dissonance, it resonates perfectly with the importance of the event and the preparations for and management of the conference, as well as the gap between the rhetoric of the UK hosts and the reality of their current domestic policy programme.

Even some of those reasonably seasoned in climate summit-watching were reaching for UN style-guide to understand whether the provisional text of the pact was being watered down or strengthened. Inside the official ‘blue zone’ of the conference, at least, people were being drawn into the vortex of verbs, in descending order of legal strength – was something, for example, being ‘requested’, ‘urged’, or ‘encouraged’?

There were so many gaps, in fact, that in spite of this being highly guarded and one of the least inclusive yet of such meetings, the whole occasion felt like a strategic exercise in memory loss.

Rich and historically high-emitting countries forgot to bring their cheque books. A pledge for financial transfers from rich to poor nations of $100 billion per year – first made more than a decade ago – still have not been met. To put that into perspective, the sum is about 1.7% of the $5.9 trillion in subsidy that coal, oil and gas received globally in 2020 according to the IMF. Sums currently on offer neither finance necessary steps in the majority world to adapt to locked-in global heating, nor pay for measures to meet human needs whilst leapfrogging development using ‘dirty’ fuels.

Worse still, some of the wealthiest countries, including the UK, which have benefitted the most historically from fossil fuels, intend to keep producing them as a report on the ‘Fossil Fuelled 5’ demonstrated. It assessed Australia, Norway, Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom, pointing out that, while coal, oil and gas production needs to drop globally by 69%, 31% and 28% respectively by 2030 to keep 1.5°C alive, these countries have plans raise oil and gas production by 33% and 27% by the same year. Coal production, meanwhile, is set to drop by only 30% – less than half of that needed.

The greatest frustration comes from the fact that the Glasgow conference was happening just at the point that globally, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, governments and whole populations had demonstrated the ability to deliver radical system and behaviour changes virtually overnight.

Gaps here are obviously being prised open by incumbent interests (such as fossil fuel-reliant companies), and these could even be seen in the sponsors of the conference, even though the UK organisers had promised a ‘clean up’, there was still plenty of evidence of special interests polluting the process. And, as one enterprising piece of research showed, when all those present with links to fossil fuel interests were added up, they proved to have, in effect, the largest delegation at COP26. In spite of this, and extraordinarily for the first time, there was actual discussion of fossil fuels themselves, as a disappointingly weak ‘phase down’ rather than ‘phase out’ of coal was agreed, and the prospect of a Fossil Fuel Non Proliferation Treaty was at least raised within the summit by campaigners.

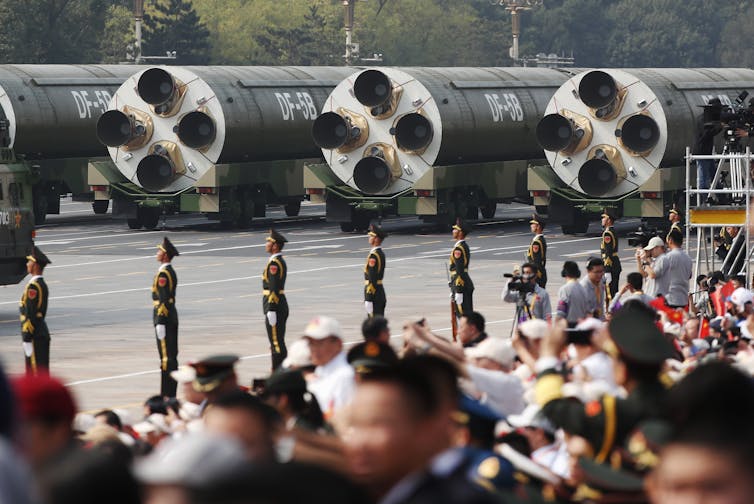

Outside of the fractured official proceedings however there was an extraordinary energy, diversity and solidarity between civil society groups ranging from those representative of indigenous people, to campaigners seeking a redirection of resources away from wasteful and heavily polluting military spending, and the world of sport where vulnerability to extreme weather events, and the possibility for mass popular mobilisation on the climate emergency, has become a major issue.

So many gaps were revealed that still need filling rapidly, that it was impossible to leave Glasgow without a sense of both impending peril – and opportunity.

The exceptionalism of the rich continues to fuel the climate crisis

Philip Webber

COP26 succeeded in delivering more urgent statements and promises but nothing sufficient to meet the target of 1.5C warming. Despite strengthening scientific warnings and evidence, the political process continued to ignore real consequences as if they won’t happen as long as they are not mentioned. Consequences include a sharp increase in mega-fires, the speeding loss of the Greenland ice sheet, and melting tundra leading to huge methane emissions. The voices of expert scientists, while present, were too quiet and less influential than several hundred fossil fuel lobbyists smuggled in who delivered soothing messages to politicians eager to hear their dulcet messages of delay – ‘not now, it’s too soon’.

While we can still theoretically avoid temperature increases above 1.5C, the national targets for 2030 made at Glasgow – if fulfilled – will only keep us to around 2.4C, with the question of whether we will improve on this depends on what is done in 2022 and 2023. Time is running out fast for necessary reductions of about 10% per year. Most current ‘Net Zero’ pledges depend on large-scale roll-out of highly suspect ‘negative emissions technologies’.

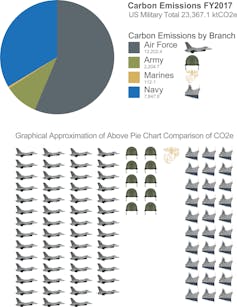

The signs are not good. Promises by wealthy nations to provide $100bn per year for climate action in the Global South have still not been met, and continue to be dwarfed by fossil fuel subsidies (see Andrew Simms’ section above). Military spending continues to expand towards $2 trillion per year, creating huge uncounted carbon emissions. Just one third of this spending could fund what is required to meet climate actions targets.

Indeed, the exceptionalism of the UK and other rich nations was on full display as they promoted a final misleading media message concentrating on a largely academic choice between ‘phasing out’ and ‘phasing down’ coal, blaming India and China, when the key problem is a continued failure to tackle the emissions of the wealthiest in society. In a globally equitable emissions reduction plan, the poorest 50% would have space to grow carbon emissions threefold while the richest 1% would reduce theirs by a factor of 30 (a 97% cut).

In Britain, the reality is that the government leads in making unfulfilled promises (also see Stuart Parkinson’s section below). For example, funding for home retrofits is weak and dispersed. We lack a comprehensive programme, coordinated at local levels. In particular, funding for the roll-out of heat pumps is grossly inadequate. There is also a belief that ‘technology’ alone will deliver the goods. There is no understanding of the need to inform, persuade and subsidise households to facilitate a transition to a low carbon future which would deliver more comfort, sharply reduced air pollution, and better health. The emphasis by ignorant sections of the media is on the costs – but there is little understanding of the wider benefits which largely outweigh them even in the short-term. Furthermore, many of the benefits are unmeasured by GDP – the long obsolete indicator that governments still prioritise. And these benefits must be shared fairly otherwise they will fail to garner the necessary public support.

Finally, some reasons to be optimistic. According to recent opinion polling – and the Climate Assembly UK – most of the UK population supports a wide range of emission reduction measures, while a huge rise in activism and informed protests continue to be our best hope to bring about necessary positive change. There has been governmental progress – just not sufficient so far. It is up to all of us to turn this around.

British sleight-of-hand disguises a lack of ambition

Stuart Parkinson

One of the things I found most striking about the outputs of COP26 was how their shortcomings reflect serious problems in the climate policies of the nation leading the process – the UK.

Arguably, the most important is that a serious lack of ambition is hidden behind warm words and incomplete targets. For a start, the UK claims to be a climate leader because it has already reduced national carbon emissions by 44% (from 1990 levels) and has a reduction target of a 68% cut by 2030 on the path to ‘net zero’ by 2050. But those reductions are based on cuts only in its territorial emissions, while the UK heavily relies upon imported goods and materials. If we look at the UK’s carbon footprint, the reduction is at least 10% less – and there is no target for the future. Then there is the government’s inability to stop new oil and gas fields in the North Sea – while we still await a planning decision on the Cumbrian coal mine. Next there is the reliance within Britain’s Net Zero Strategy on speculative and controversial technologies – such as redesigned nuclear power stations, blue hydrogen, and zero emissions aircraft – while tried and tested technologies such as home insulation and onshore wind farms remain inadequately supported (also see Philip Webber’s section above) and behaviour change is entirely missing (see Jan Maskell’s section below). On the subject on international finance, Britain has retained its commitment to spend £11.6bn on climate-related aid over five years from 2021 – which is very welcome – but this should be measured against a reduction of £18bn of other overseas aid (in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic) and an increase in military spending of over £20bn (both of these over only a four-year period).

These shortcomings have numerous parallels within the COP26 agreements, and I list a few key examples here. There is the continuing inability of the wealthy nations to provide adequate international climate finance (see Andrew Simms’ section above), while no funding at all has yet been agreed for ‘loss and damage’. The largest coal-rich nations refused to join the agreement to phase out coal, while most – including Britain – refused to join the alliance aimed at ending oil and gas production. Meanwhile fossil fuel subsidies were only briefly and inadequately covered in any of the agreements, and mention of behaviour change was virtually absent. Perhaps most disturbing of all was the inability to deal with the huge inequality between the emissions of the richest 1% and the poorest 50% (see Philip Webber’s section). However, thanks to SGR and our collaborators, military carbon emissions received more media attention – but again this was not reflected within any formal policy.

For me, hope for the future comes from society’s proven ability to undertake rapid transition when ‘social tipping points’ are reached – we did it in the pandemic and we can do it again (see Andrew Simms’ section). We need to keep pushing for this.

Behaviour change: a missed opportunity

Jan Maskell

How important is behaviour change compared to technological solutions in tackling the climate crisis? The reported outcomes of COP26 seem to focus on techno-solutions, such as carbon capture and storage, to by themselves reverse the effects of climate change. Although some of these may hold promise, overconfidence in them can lead to inaction in other areas with better proven effects. The hasty withdrawal – in October – of the UK government-commissioned report Net Zero: principles for successful behaviour change initiatives signalled a reluctance to even consider behaviour change as part of a solution. Behaviour change can be interpreted at different levels: individual, societal and organisational – all of which have a vital part to play in achieving net zero. The paper stated that ‘Achieving Net Zero requires significant behavioural change, including rapid and widespread adoption of new technologies, and a significant reduction in demand for some high-carbon activities such as flying and eating ruminant meat and dairy’. Drawing attention to these specific behavioural changes seems to be particularly challenging to a political system that currently does not discourage flying – as seen in the recent budget, where high carbon emitting domestic UK flights will be subject to a new lower rate of Air Passenger Duty from April 2023 thus encouraging the activity. The Committee on Climate Change has noted that 62% of future emissions reductions depend on behaviour change – 53% of this will be through adopting low carbon technologies, such as heat pumps and electric vehicles and the other 9% reducing demand for high-carbon activities including aviation, ruminant meat and dairy, wasted food, and car travel. The evidence on the value of behaviour change therefore seems robust.

The report also considered the upstream, downstream and midstream level actions required for a route to net zero which is both politically feasible and minimises the burden on citizens. This path involved interventions to change the functioning of the socio-economic system, change the ‘choice environment’, and encourage individuals to make different choices. As almost all government actions and policies intend to lead to behaviour change at one or more of these levels, whether through commercial incentives, taxes, providing information such as comparison tools or rating systems, or demonstrating widespread social norms and values – so what was the reason to withdraw this report? One response is that the politicians feared a right-wing voter backlash against the perceived planned withdrawal of their gas boilers and petrol cars, and being told not to fly or what to eat. Another possibility is lobbying, such as from the meat and dairy industries and aviation sector, to avoid behaviour changes that would affect them.

As so many members of the public now want to take climate change action and develop new habits (see Philip Webber’s section above), and would benefit from this being made easier and simpler for them through this report’s proposed alignment of policies, revised infrastructure, incentives to business and new social norms, the withdrawal of the report and the avoidance of the policies it recommends is at odds with the need to tackle the climate crisis. The resulting reliance on techno-salvation seems wildly misplaced.

Andrew Simms is SGR’s Assistant Director, co-ordinator of the Rapid Transition Alliance, and co-director of the New Weather Institute.

Dr Philip Webber is SGR’s Chair, and a former head of local government energy and environment programmes in north-east England.

Dr Stuart Parkinson is SGR’s Executive Director, whose background includes a PhD in climate science and a period as an expert reviewer for the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Dr Jan Maskell is SGR’s Vice-chair, a chartered psychologist, and Chair of the Going Green Working Group, part of the British Psychological Society.